REVIEWED: Daniel Blaufuks | All the Memory of the World, Part One

By Sandra Camacho

All the

Memory of the World, Part One, a show dedicated to memory,

literature and the ever-expanding archive that is the internet, opened the SONAE-sponsored new

cycle of exhibitions at the National Museum of Contemporary Art – Museu do

Chiado (MNAC) in Lisbon. Curated by MNAC Director David Santos, it features works by Daniel Blaufuks (b. Lisbon, Portugal, 1963) that are deeply connected to the artist’s

PhD research, which he is carrying out at the University of South Wales.

Having worked in previous projects on the subject of the Holocaust – Under Strange Skies (2002) and Terezín (2007) – Blaufuks continues his

exploration of the viewer’s perception of reality through filmic and photographic images and archive footage. In All the

Memory of the World, Part One, Blaufuks returns

to German academic W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz

(2001), a novel about a Jewish refugee who arrived in Wales as an infant in 1939. In the story, we learn of the main character’s (Austerlitz) history and the effects the 1944 Nazi

propaganda concentration camp film Thereseindstadt. Ein Dokumentarfilm aus dem Jüdischen Siedlungsgebit as well as other archive

images from various European libraries had on his childhood memories. As such, archive footage and

documentary photography reflect how images can entomb memories.

|

| Daniel Blaufuks, All the memory of the World, Part One, installation view at MNAC, 2014-15. Courtesy of Vera Cortês Art Agency |

Additionally, Blaufuks looks to W, or the Memory of Childhood (1975), a semi-autobiographical

work of fiction by George Perec. The French author interprets

his childhood memories, pointing out that many of these are simply borrowed or outright false. A member of

the French group Oulipo, Perec used constrained writing techniques, a reference

we see reflected throughout the exhibition, not least in the opening sequence

of text-based images whereby wordplay points to tragic similarities between Austerlitz

and Auschwitz or Theresienstadt and Theresienbad.

|

| Daniel Blaufuks, As If, 2015. video still |

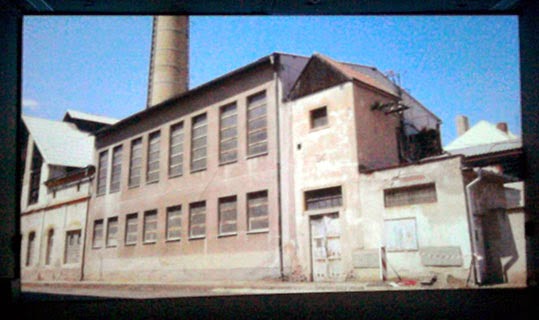

A particularly powerful

element of the exhibition is the 4h35m-long video As If (2014). It intertwines modern day images of the Czech town of Terezín

(the name Theresienstadt took on after WWII) with popular fictional depictions

of the concentration camp. Among the artificial recreations, stand the 1978 mini-series

Holocaust and the aforementioned 1944

Nazi propaganda film.

|

| Daniel Blaufuks, As If, 2015. video still |

In the midst of sunny, empty streets and buildings, the

sounds of steps, human voices and train engines taken from films populate the modern

Terezín like ghosts of the past. In one shot, school children are toured

through the abandoned camp whilst taking photos and idly chatting, and in another, the viewer is faced with the same spaces filled with people re-enacting

scenes whose accuracy we will never really know. At the same time, by using footage

from the staged Nazi film alongside images from Hollywood productions, Blaufuks confronts our perception of truth and the construction of a collective memory

based on fictional representations. As such, the piece reflects on how we

remember, forget and believe we remember.

|

| Daniel Blaufuks, Archive, 2014. Courtesy of the artist |

The idea of a constructed

memory based on mediation is a common thread running across the works. Although many of Blaufuks’ works are based on archival images and

found footage, these

are generally intimately connected to the artist as they tend to come from from his family records, particularly from Blaufuks' German Jewish grandparents who sought refuge in Lisbon during WWII.

In All the Memory of the World, Part One a shift is nevertheless made to include and research images from the biggest archive known to man: the internet. By assembling images found online to create his compositions or “visual maps” as he describes them, Blaufuks presents the viewer with a representation of the intricate variants depicting a single concept. Today there are millions of images that can be associated with the Holocaust and whether fairly or in poor taste, due to the internet, these become of equal value or importance. By presenting the images in an almost free-association style, Blaufuks illustrates the democratisation that the archive and now the internet can have on the image and its reading.

In All the Memory of the World, Part One a shift is nevertheless made to include and research images from the biggest archive known to man: the internet. By assembling images found online to create his compositions or “visual maps” as he describes them, Blaufuks presents the viewer with a representation of the intricate variants depicting a single concept. Today there are millions of images that can be associated with the Holocaust and whether fairly or in poor taste, due to the internet, these become of equal value or importance. By presenting the images in an almost free-association style, Blaufuks illustrates the democratisation that the archive and now the internet can have on the image and its reading.

|

| Daniel Blaufuks, The way to Auschwitz, 2014. Courtesy of the artist |

All the Memory in the World,

Part One therefore builds upon Blaufuks’ previous work

and the references that form its basis. Similarly to reading either Sebald or Perec, the gallery visitor leaves wanting

to delve deeper into the presented subjects and return knowing a

bit more about these.

Daniel

Blaufuks | All the Memory of the World, Part One

National Museum of Contemporary Art – Museu do Chiado

11 December 2014 – 22 March

2015